Not a member of Pastebin yet?

Sign Up,

it unlocks many cool features!

- Empowering Girls in the

- Transnational W.I.T.C.H. Magazine

- and Comic Series

- Simona Di Martino

- Abstract: The Italian-made comics series W.I.T.C.H. and the homonymous mag-

- azine enjoyed global success. The series tells the story of five girls who discover

- they have magical powers and are called on to save the universe from evil forces. I

- investigate this transnational and transmedia series and explore how girls’ empow-

- erment is pursued through the trope of the teenage witch in the comics’ storyline,

- revealing the hybridization of manga, European, and Disney graphic styles and

- themes, and in the magazine itself where the editors use techniques of engage-

- ment with readers (surveys and quizzes, problem pages and letters from readers,

- DIY pieces, and diary-like pages). This analysis involves scholarship on Girlhood

- and Cultural Studies and serves as a springboard for further investigation.

- Keywords: adolescence, comics, Disney, Euromanga, Girl Power, magazine,

- transnational, witches

- A New Comics Series for Teen Girls

- From adult comics (Castaldi 2010) to graphic journalism (Fasiolo 2012),

- from Topolino (Gadducci et al. 2020) to Disney Italia’s productions (Tos-

- ti 2011), and from studies on single characters such as Tex Willer (Leake

- 2018), to reviews of the most representative comics artists (Prandi and

- Ferrari 2014), the Italian fumetto (comics book) is increasingly attracting

- academic attention. While until the early 2000s, surveys of Italian comics

- featured mainly male authors and characters (Pizzi 2004), more recent and

- specialized studies devote space to female artists and characters (Bonomi et

- al. 2020; Zanatta et al. 2009). In examining W.I.T.C.H, both the magazine

- and the comics series inside it, I aim to build on these studies and contrib-

- ute to the growing critical movement of women in Italy for the recognition

- of comics and female characters. To date, Marco Pellitteri has been the only

- scholar to analyze W.I.T.C.H. critically by focusing on the comics series and

- effectively examining its success and hybridization with foreign traditions

- regarding comics (Pellitteri 2009, 2018).

- W.I.T.C.H. was first published in Italy in October 2001, produced by

- Disney Italia and created by Italian authors, artists, and editorial staff. In

- his article published in the online magazine Fumettologica, Andrea Fiamma

- (2021) retraces the origins of the comics and explains that children’s au-

- thor Elisabetta Gnone, then the director of the girls’ publications division

- at Disney Italia, was commissioned to design a product aimed at young

- teenage girls, a segment of the public not yet targeted then. Gnone con-

- ceived the idea of a story centered on a group of adolescent girlfriends with

- magical powers and sought artists to bring her idea to life. She involved

- Barbara Canepa, a comic artist and painter who studied at the Disney

- Academy and was already working as an illustrator for the Disney maga-

- zine La sirenetta (The Little Mermaid), and Alessandro Barbucci, a former

- teacher at the Disney Academy with significant experience and important

- projects under his belt.

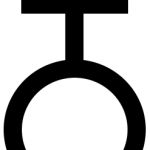

- Using witchcraft as a metaphor for adolescence, W.I.T.C.H. follows the

- adventures of five teenage girls, Will, Irma, Taranee, Cornelia, and Hay Lin,

- who discover they have magical powers and are tasked with protecting the

- universe from evil forces while balancing this with their everyday lives. The

- aim of the project was not only to craft a product for young girls, but also to

- innovate graphic designs and involve characters beyond the standard Dis-

- ney roster like Mickey and Minnie Mouse, and Donald and Daisy Duck.

- W.I.T.C.H. was indeed the first Disney publication conceived of as a mag-

- azine for adolescent girls featuring a comics series with human characters

- instead of anthropomorphized animals (Tosti 2011; Zanatta et al. 2009).

- According to Mara Pace, the W.I.T.C.H. magazine sold over 250,000

- copies per month in Italy in 2004 and enjoyed considerable popularity

- worldwide (Corriere della Sera 2004). In Issue 34 (January 2004), the ed-

- itorial team celebrated the new year by dedicating space to ‘W.I.T.C.H.

- in the world’ (48–49). There, they show that the adventures of the five

- magical girls were translated into more than 30 languages and distributed

- in 51 countries from China to Iceland. In Issue 50 (May 2005), the mag-

- azine’s director Valentina De Poli celebrated millions of W.I.T.C.H. fans

- worldwide, testifying to an increase in the publication’s reach, now printed

- in 63 countries. as a magazine and a comics series primarily directed atSIMONA DI MARTINO

- 48

- adolescent girls. In this analysis, I assess how the trope of the teenage witch

- and the editors’ engagement with readers contribute to the representation

- of empowered adolescent girls and invites reflections from the perspective

- of Girlhood Studies.

- Transnational Comics

- According to Kraenzle and Ludewig (2020), comics are defined as transna-

- tional when they provide the reader with “narratives, histories and imaginar-

- ies that transcend national boundaries [and when] practices of comics pro-

- duction [are] indebted to multiple comics traditions” (2). The W.I.T.C.H.

- comics series evidently manifests signs of transnationality, boasting an ap-

- parent hybridization of styles, themes, and imageries with Japanese manga,

- Disney, and European graphic styles (Pellitteri 2009).

- To design the W.I.T.C.H. comics, artists Canepa and Barbucci em-

- ployed a graphic fusion style called Euromanga that blended the Western

- graphic tradition with Japanese manga (Pellitteri 2018). According to Ar-

- ianna Rea, a Disney character designer and teacher at the Scuola Romana

- dei Fumetti, the Euromanga style originated in Europe in the early 2000s,

- and, in Italy, it developed primarily in the Disney publishing world (Scuola

- Romana dei Fumetti, 2022). Japanese traits that characterize Euromanga

- typically include

- physical features of the characters (large eyes, pointed chin, young-looking faces,

- bodies often slender and thin), the not orthogonal layout of the panels, the fre-

- quent use of graphic conventions like kinetics lines, and the brevity of the di-

- alogue in comparison to the overflowing literariness of most popular Western

- comics. (Pellitteri 2010: 432)

- The W.I.T.C.H. series incorporates features typical of manga regarding

- characters’ looks, page design, decorations, themes, and concepts. In terms

- of characters’ appearance, the W.I.T.C.H. group leader Will is inspired by

- the young cyborg Alita from the homonymous dystopian manga (1990) by

- Yukito Kishiro. Will and Alita have a similar physical appearance and hair-

- style along with stylish attire. However, Barbucci refined the character of

- Alita for the younger audience for whom Will was conceived, refusing Ali-

- ta’s futuristic and cybernetic appearance and intense gaze (Locatelli 2021).

- Recurring manga features include dynamic page design with characters

- coming out of panels along with irregular borders, as exemplified in Issue

- 22 in which Cornelia, crying and drenched from running in the rain, enters

- EMPOWERING GIRLS IN THE TRANSNATIONAL W.I.T.C.H.

- 49

- her room and gradually remembers small events from the past that a spell

- had caused her to forget. The emergence of memories in a fragmented and

- painful manner is graphically reflected in irregular panels of different shapes

- and sizes resembling shards of glass, while the figure of Cornelia crying ex-

- pands across the background in a full-page spread. Fluttering flowers, often

- seen on the covers of the W.I.T.C.H. magazine (see Issues 24, 26, 38, 40,

- 47, 48, 51, 54), are also features reminiscent of the floral motifs common-

- ly found in shoujo manga, a genre of Japanese comics and graphic novels

- aimed primarily at a young female audience.

- On a visual and conceptual level, W.I.T.C.H. features the girls’ transfor-

- mation into adult versions of themselves; they are taller and more feminine

- than their everyday appearance, thus adhering to the main theme of many

- majokko genre. Majokko is a subgenre of Japanese fantasy media that targets

- “female prepubescent viewers” featuring magical girls and generally involv-

- ing an “elaborate description of metamorphosis that enables an ordinary

- girl to turn into a supergirl” (Saito 2013: 144). These narratives are usual-

- ly developed in manga and then transformed into anime. Jason Thomson

- (2007) credits Himitsu no Akko-chan (1962) and Sally the Witch (1966) with

- being the first magical girl productions, later followed by Creamy Mami

- (1983), Sailor Moon (1991), and Magical Do-Re-Mi (1999). These anime

- series reached immense success in Italy, thus shaping the imagery of young

- viewers (Pellitteri 2010). Pellitteri (2009) asserts that “the basic narrative

- structure of the [W.I.T.C.H.] series is a recapitulation of the Japanese for-

- mula of a group of five witches, each with different and complementary psy-

- chology, color, totemic symbol, power and dressing style, united together in

- a team” (389). Both Canepa and Barbucci declared that the Japanese Sailor

- Moon series served as a model (Locatelli 2021). Despite resembling Sailor

- Moon, which also features a group of female friends with magical powers,

- Pellitteri maintains that the protagonists of W.I.T.C.H. are characterized

- by a different distinct aesthetic identity given by Gnone’s Italian creativity

- and sensibility, along with the plasticity of the art by Barbucci and Canepa.

- W.I.T.C.H. features three Caucasian girls, an African American girl, and a

- Chinese girl, showcasing a more inclusive and diverse cast than Sailor Moon

- and actively promoting graphic narratives that challenge nationalist, top-

- down, and white-and-male-centered representations of Italian culture.

- W.I.T.C.H’s five protagonists have their own identifying marks, person-

- alities, fashion styles, and elemental powers (Irma controls water, Taranee

- fire, Cornelia earth, Hay Lin air, and Will energy). Will has red, short hair in

- a bob cut, and big brown eyes. She likes wearing practical clothes like wide

- SIMONA DI MARTINO

- 50

- pants and hoodies with zippers. Taranee, shy and determined, is a Black girl

- of African American descent. She wears glasses, has blue-black hair and loves

- streetwear fashion. Irma is a very expressive and witty girl with shoulder

- length hazel, wavy hair, and big greenish-blue eyes. Her desk mate is Hay

- Lin, a Chinese girl with long dark hair tied in pigtails who wears brightly

- colored outfits she personally designs. Cornelia is tall and slender with long

- blond hair and light blue eyes and is very stylish and elegant.

- Another characteristic derived from manga is the modern portrayal of

- female characters who are not only independent and no longer defenseless

- but also assist male characters who are often fragile and in need of help

- (Pellitteri 1999). The W.I.T.C.H. series includes several episodes featuring

- the five girls rescuing boys. In Issue 11, the girls support their schoolmate

- Martin, demonstrating their teamwork and solidarity against bullying; in

- Issue 15, Cornelia restores her beloved Caleb to life after he is turned into

- a flower by an enemy; and in Issue 62, the girls free Matt, Will’s boyfriend,

- from a magical diary that had imprisoned him, just to name a few examples.

- Finally, from the Japanese majokko tradition W.I.T.C.H. derives the mi-

- crocosm of feelings that potentially interest teenagers. Young readers could

- easily project themselves onto heroines who transform into young women,

- embodying a transition from childhood to maturity both physically and in

- terms of independence. In an interview published in the magazine Scuola

- di Fumetto (2010), Barbucci confirmed that the W.I.T.C.H. project aimed

- to reproduce adolescence in its complexity and in a realistic manner like

- Japanese authors generally represent it. Magda Erik-Soussi confirms how

- realistically the Japanese represent adolescence: “Sailor Moon’s feminine

- core was raw and honest, putting focus on the huge, mostly female cast’s

- struggles with morality, friendship, jealousy, sexuality, vulnerability, and de-

- sire to protect loved ones” (2015: 26). Pellitteri effectively summarizes the

- W.I.T.C.H. transnational phenomenon in saying,

- Gnone had adapted the scheme of the action team, which is far older than Sail-

- or Moon, to cover important themes for girls such as growing up and moving

- from childhood to adolescence, with all the many temperamental, emotional,

- and physical evolutions that such change involve. The art has been able to per-

- fectly translate these themes, portraying five fashionable girls having their own

- insecurities and individualities while still maintaining . . . a wide set of stereotyp-

- ical characteristics in which young female readers can see themselves. (Pellitteri

- 2009: 391)

- However, as Nicolle Lamerichs states, “It would be wrong to portray this

- dynamic solely as an influence from Japan’s side” (2015: 76). Japanese cre-

- ators have also been influenced by American culture and have produced

- EMPOWERING GIRLS IN THE TRANSNATIONAL W.I.T.C.H.

- 51

- manga and anime that, in turn, have entered Europe, mediating both Jap-

- anese and American cultures. Lamerichs explains that “Osamu Tezuka, Ja-

- pan’s preeminent author, was inspired by Disney productions in his work”

- (2015: 76). The American television shows Bewitched (1964–1972) and

- I Dream of Jeannie (1965–1970) have proved influential for the Japanese

- witch storylines set in modern urban settings, from Sally the Witch (1966)

- to the transforming Sailor Moon’s girls in the 1990s (Pellitteri 1999; Saito

- 2013). The mediated trope of the teenage witch prompts further investiga-

- tion, to which I now turn.

Advertisement

Add Comment

Please, Sign In to add comment